The Snippet is a Weekly Product Management Newsletter for aspiring Product Leaders.

The past few months have been pretty busy at work. We’ve started an exercise where we are evaluating a product - currently manufactured in our European & North American factories — to be manufactured in our Asian factories to serve the regional markets.

There have been several meetings, planning sessions, and discussions to plan every aspect of the manufacturing move. For instance, How many units might we sell out of this factory? How long will zero to starting up production take? What the supply chain/sourcing strategy will look like? And more.

This has taken the bulk of my brain cycles & time over the past few months, and I was finally able to sit down and document some key observations I’ve made during the course of this exercise.

Minimizing surprises

On the front end, such an exercise starts with having a solid business case for regionalizing a product. After all, this manufacturing move would require a multi-million dollar investment from the company. But as it turns out, the business case is actually the easy part.

The hard part is planning the execution of a project like this one. There are a ton of gnarly details that must be thought through in advance so execution is as smooth as possible—mitigating risks of costly speedbumps. With complex projects such as this one, a strong plan that minimizes surprises is often the difference between success and failure.

Not everyone is a natural when it comes to planning

It’s in the nature of planning that you are trying to predict/estimate something in the future and then you are trying to layout step-by step everything that’s needed to get there. For instance, right now we’re trying to estimate our costs of manufacturing this product in Asia. It’s a tedious exercise. Manufacturing cost estimates are dependent upon many other factors —most of those factors are also best estimates at this point.

There is a reason not everybody is a good planner. In fact, most people aren’t. People with natural dominance in the back-left part of the brain are most comfortable making linear plans and following them. If you are the creative type or a non-linear thinker—it’s often hard to create & follow a linear plan. Planning also involves being comfortable with risk. It involves being able to zoom into the complicated details without losing the 50,000 feet perspective, the big picture.

As I watch my own team go through what we are calling the manufacturing regionalization planning exercise, two clearly distinct sets of people emerged.

There are the ones that are the risk-takers, keying in and signing up for aggressive timelines and raring to get started. They are focused on the future state, almost living in it. They are the nonlinear thinkers, the idea generators, and problem solvers, and ultimately the prime movers of any new initiative, such as this one. In organizations, they also happen to be the most celebrated lot.

And then there is this other set of people. Feet firmly in the present, in the here and now, and thinking about the immediate next step and nothing beyond. These are people that can sniff out a problem before it occurs. They are the ones with the bullshit sensors, keeping the team from getting ahead of themselves. They are the ones flagging the risks with the plan and making it visible to everybody.

Unfortunately, in many organizations, people who flag risks are labeled as “too conservative” or the “problematic ones”. But make no mistake, it is because of this set of people that complicated projects are successful. They are the “problem preventors” and pressure testers of the big plans.

Kahneman & Tversky & the Planning Fallacy

Let’s talk about research around how hopeless average human beings are at planning (anything). The Planning fallacy was first postulated and by friends and behavioral psychologists Daniel Kahneman & Amos Tversky —and it says — human beings, when we make predictions about how much time will be needed to complete a future task, consistently underestimate it.

And if that’s not enough embarrassment for us, we do it even though we’ve had prior experience with a similar task. And this human fallacy is not just limited to time. It extends to estimating costs and assessing risks, and other important aspects of planning. In other words, most people are by design bad planners.

For instance, a bunch of psychology students was asked how long it would take them to complete their senior theses. These students had all submitted multiple theses in the past as part of their coursework —so everybody had some prior experience around the task at hand.

The average estimate by the group was 33.9 days. their best-case estimate was 27.4 days. And their own worst-case estimate was 48.6 days.

so what happened? The average actual completion time of the theses was about 55.5 days. Yup.

Humans are ridden with Cognitive Biases

There is a lot of research to try to figure out why we suck at planning—and experts have found that humans are the rabbit hole of cognitive biases, both conscious but mostly unconscious. Here are a few biases that directly and negatively affect our planning chops.

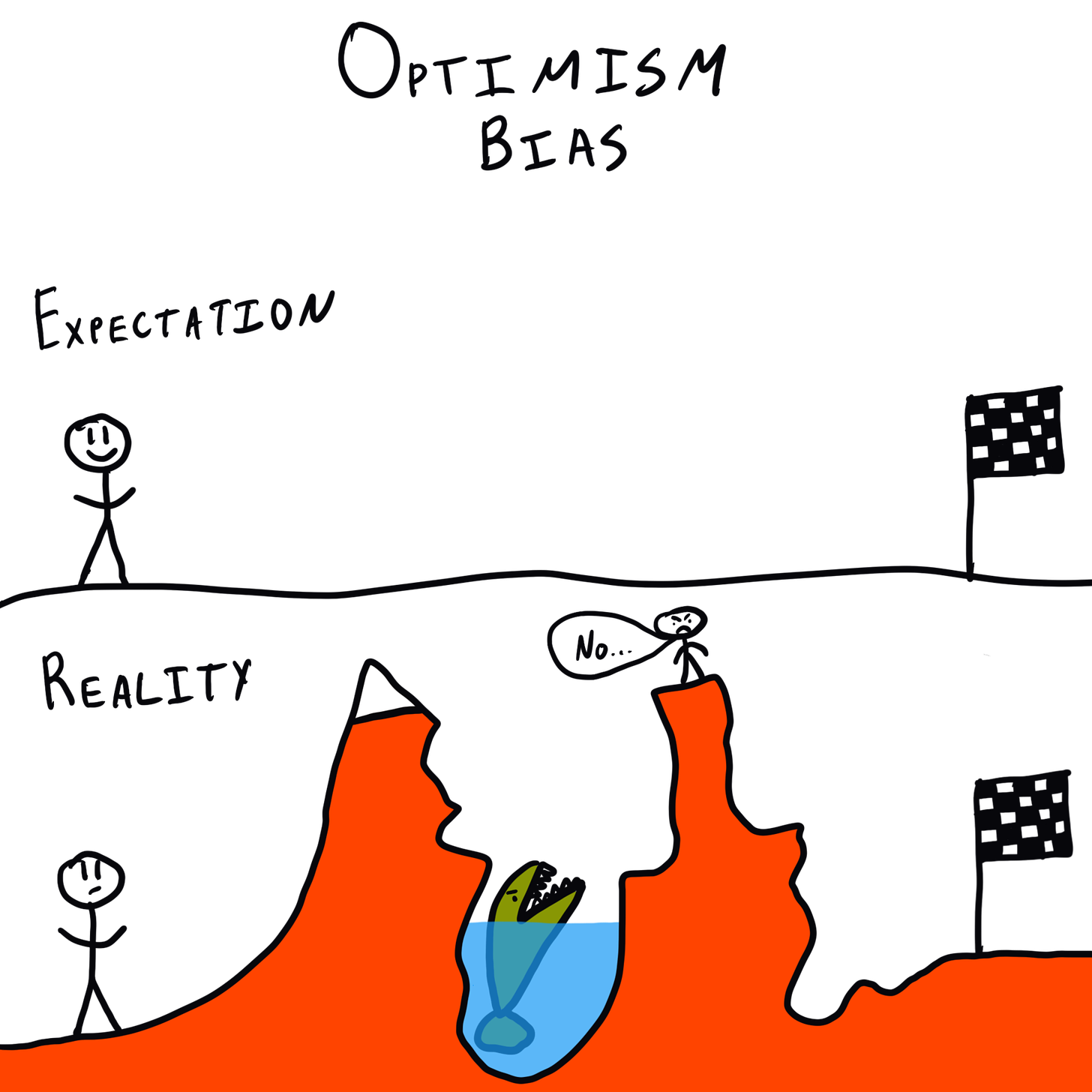

Optimism Bias: Most planners (even the most conservative of them) show something termed as the optimism bias, especially when it’s a task they are involved in—or worse still— leading.

Optimism bias is the tendency to overestimate our likelihood of experiencing positive events and underestimate our likelihood of experiencing negative events. This leads planners to gravitate towards best-case scenarios and ignore worst cases.

Wishful Thinking: Wishful thinking seems like something that wouldn’t happen to rational planners, but research says otherwise. In fact, many of us perceive the world as we think it is— rather than based on evidence, facts, and truths. We do so mostly because we think “ it’s so good, it must be true”. Moreover, because we’ve never experienced the alternative scenarios ourselves—we think they don’t exist. When we let our wishful thinking get the better of us amidst a planning exercise, we’ve let our guards down and introduced risk to the project.

Self Serving Bias: If you’ve ever been in sales, you have probably come across salespeople who will ascribe a good sales month to their own hard work and superior sales strategy —but they’ll be quick to blame poor sales performances on the market, product issues, etc. Classic self-serving bias in action.

Self-serving bias a result of people wanting to manage how others think of them. This bias leads us to over-index on our ability to drive successful outcomes and establish causal relationships with success where there in fact maybe none. In the context of planning —self-serving bias leads individuals to reject and /or ignore negative outcomes in the past and blame it on external factors other than their own competence. This can also lead to underestimating the time, costs, and risks of a project.

Strategic Misrepresentation in Planning

Our behaviors are indeed a function of our own cognitive strengths and biases, but there are other factors that influence how a project is planned, presented, approved, and executed. One of the things that happens a lot with large complex projects, and in large organizations is “Strategic Misrepresentation”.

Ever been in a cross-functional project where the business development manager is trying to overstate the benefits of a project to get it approved? Ever been in situations where supply chain teams are sandbagging costs to make sure they can deliver on aggressive cost reduction targets? In both cases, people are misrepresenting the real situation. They are putting themselves and/or their teams before what’s best for the organization.

So why do people misrepresent?

Misrepresentation happens due to several factors —sometimes it’s used as a de-facto tool to navigate org politics (hence strategic). At other times, it’s simply due to principal-agency problems in organizations where incentives are misaligned.

For instance, the overenthusiastic business development manager might be eyeing their next role, and perhaps if they can get the project approved —it’ll make their case for being promoted stronger. The supply chain team may artificially inflate costs so that they can sign up for aggressive cost reduction targets and still have a shot at achieving their bonus.

Misrepresentation is a symptom of deeper alignment issues in organizations - raising its ugly head in high stake situations and projects. Needless to say, to foster a strong planning culture and develop solid decision-making capabilities, misrepresentation must be minimized.

Getting the basics right

Strong effective planning involves a lot of focus, hard work, and cross-functional alignment. The usual strategy is to say '“Let’s bring data to the table and make decisions based on data” —sure, but that’s not enough.

Planning leaders must constantly watch out for cognitive biases, challenge themselves and their teams on assumptions behind their proposals. They must get into the weeds of the most critical details of the plan and minimize information asymmetry. There is no such thing as “planning from a distance”. One must either get their hands dirty at planning time or brace for unexpected (and nasty) surprises at execution time.

We live in times where rapid planning and decision making is celebrated, as it should be. But our plans (no matter how quickly they’ve been put together) must take into account how to deal with incomplete information and how to spot misrepresented and biased information. The former is transparent and creates known risks, the latter generates unknown unknowns, much harder to deal with. In the end, we must all strive for rapid and efficient decision-making— but when we have the luxury of time, let us use it to make higher quality ones.

I hope you enjoyed this post. You can follow me on Twitter where I share learnings on managing and building products.

👋 Thanks for reading!

-Abhi

The Snippet is a Weekly Product Management Newsletter for aspiring Product Leaders.

This post has been published on www.productschool.com communities.